Christi Marie Hannah was well into training to run in multiple rigorous obstacle courses this year as a returning contestant on the “American Ninja Warrior” television show when she was unexpectedly diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia, a potentially deadly heart disorder.

Hannah is a single mother with three children who grew up in Fairbanks and now splits her year between Alaska and Iowa, her current home at this time of the year, where she coaches sports for kids and is a dental hygienist.

Hannah is the third Alaskan to be on the show, following Nick Hanson of Unalakleet and Nate DeHaan of Bethel.

Christi Hannah with her kids Emily, 11, Logan, 4, and Michael, 10. Courtesy of Christi Hannah

The series, a spin-off of the Japanese television show “Sasuke,” has contestants compete in a timed obstacle course testing speed, strength and balance. The contestants with the most successful runs through the course move through multiple phases of the show, from city qualifiers, to city finals, to nationals, where the ultimate goal is to beat the “Mount Midoriyama” obstacle course in Las Vegas and become the next American Ninja Warrior.

Athletic fitness is paramount in the contest and working out has been a major part of Hannah’s life.

She would try to be in the gym at least two hours per day for four to five days per week. Even when she can’t make it, she and her children did workouts together at home. She began training for “American Ninja Warrior” while in Missouri in 2017 as a kind of half workout goal, half bet with her trainer. In 2018 she was a tester for the Minneapolis obstacle course, and in May 2019 she made her first run as a bona fide contestant, just before her 30th birthday.

Hannah made it past the Seattle/Tacoma qualifiers last year, placing fourth out of the top five women competitors, but didn’t make it past the city finals.

She kept on training. Then everything stopped.

Christi Hannah coaches children and has maintained an optimistic mindset, despite her recent setbacks. Courtesy of Christi Hannah

A sudden change of plans

“Two months ago I pretty much collapsed on a run,” Hannah said in an early January telephone conversation from her Iowa home. “I’m not a runner and I’m not going to pretend that I am, but it’s kind of my endurance. I force myself to do so many miles.”

At the time, she was in Iowa, and Hannah’s Apple Watch logged her heart rate at 195 beats per minute. The American Heart Association notes that the target heart rate for 30-year-olds exercising is 95-162 bpm, while the average maximum heart rate is 190 bpm.

“So on that run I was full force running and the ground started moving and just black came to my eyes and I just kind of melted to the ground.”

She curled up and told the people she was running with to give her a minute to regroup. She finished that run, but when she described her symptoms to a doctor, she was told to come in immediately.

Doctors tested her for diabetes, asthma, low electrolytes and — despite Hannah being highly fit — they checked her heart. The electrocardiogram came back normal, but her doctor wanted more tests.

Hannah was given a heart monitor in mid-December and was told to do everything she could in the next 24 hours to make her heart do whatever it might have done when she collapsed.

So she went to the gym for two hours, where she decided to run to try to trigger the same response. It worked. Her doctors were monitoring her heart during the workout and called her to tell her to stop immediately and return to the hospital.

Ultimately it was an electrophysiology cardiologist who diagnosed Hannah with ventricular tachycardia. Something was very wrong in her heart’s electrical pathways.

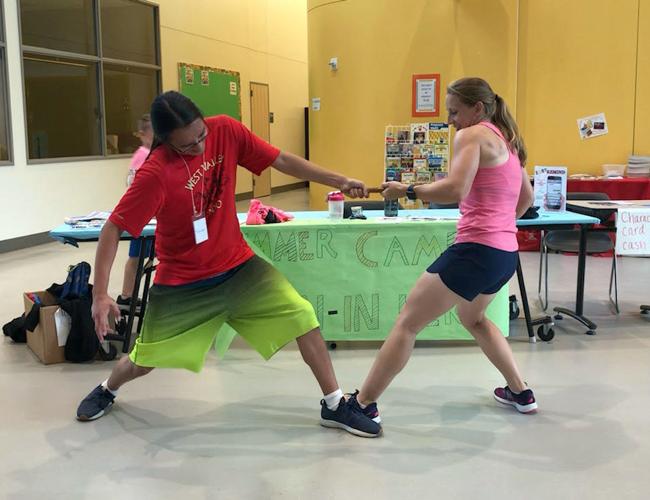

A student named Trevor teaches Hannah some Alaska Native games, including the stick pull. Courtesy of Christi Hannah

Mixed signals

Hannah’s doctors, using a process called cardiac ablation, wanted to fix her heart by destroying the part of it that wasn’t functioning properly.

When the day came for her procedure, everything went as planned — almost.

She went to MercyOne hospital in Waterloo, Iowa, where doctors planned to insert a catheter in each of her femoral veins, located in the thigh, and then thread them up to her heart. The idea was to shock her heart so they could see which part of it was failing in order to destroy that tissue.

“It was interesting to see all of the little electrodes in my heart, just watching the video of it, you know, and seeing how he would control each one, setting them up and down and how they would need to go,” Hannah said.

Her doctor talked with her throughout the procedure, asking Hannah what she felt as the test proceeded.

They would shock her heart until it spiked and watch as her heart rate dropped and recovered.

At one point her heart rate rose above 280. Hannah said it felt as though someone was crushing her head but at the same time they were turning a knife in her chest. She could feel her heart spasming.

That was when they had to stop the process.

Hannah said her doctor came over and told her, “We have you at the most dangerous levels we can put you at and it’s not doing anything.”

Somehow, despite multiple readings on heart monitors while she was training, doctors didn’t find what they were looking for.

Christi Hannah does a handstand to show her Alaska pride.

The next obstacle

Going into the procedure, Hannah said she wasn’t afraid to die but was afraid to leave her children behind.

She hasn’t talked about the subject with the kids she coaches at work beyond telling them she had to have an operation, but her own three children are a different story. Her oldest child, Emily, is 11, while the younger two, Michael and Logan, are 10 and 4.

“With my own kids, they know quite a bit more about what’s going on, but I try to keep it pretty G-rated to where it’ll be OK. Kids are pretty smart,” Hannah said, after the ablation attempt.

The children have seen her on the worst days, when she has trouble getting up. “So for them, it’s definitely been scary for them.”

Although the ablation was inconclusive, it did bring some positivity. But it also brought some uncertainty.

Initially she was still planning to continue training following the ablation. She said there was some speculation during the procedure that, because of her rigorous training, her heart has the ability to recover from her episodes of ventricular tachycardia.

“There’s a good side of that, meaning that I won’t go into cardiac arrest,” she said. “They said that was surprising and that I can continue to train with my heart the way it is.”

The issue is figuring out what to do from here, though. It took some time for the catheter entrance sites to heal before she could go to the gym. Once they did, Hannah tried to work out again.

“I can’t do push ups consistently,” she said. “I can do 12 and my body was shaking so bad I couldn’t hold up. So I had to stop and usually I do 70 to 80 straight through.”

She hasn’t risked a workout again.

“From the day that I tried, that was the only one I tried and that was scary enough for me that I’m just not going to push it.”

She said she’d like to try again, but she’s leery of doing anything at this point. Hannah says she can’t even stand at work for long periods of time.

Another ‘Ninja’ shot?

As of right now, her next run on the “American Ninja Warrior” obstacle course is up in the air. She is supposed to compete in St. Louis in May.

If the heart trouble continues, she said the show’s producers probably won’t allow her to participate, but she doesn’t know yet.

“I’m still not giving up hope, if that says anything,” she said. “People keep asking if I’m still going to compete this spring and I’m like ‘Yep, I am.’”

The optimistic attitude is a bit of a theme for her.

She didn’t talk about what had been happening for months after the symptoms started. Then, one day in late December, Hannah made a post on her Facebook, telling people what had been going on. Ninja competitors posted many positive comments.

“Sometimes reality’s not the best part, but you can make a positive out of it,” Hannah said.

That was before the procedure took place.

On Jan. 31 Hannah emailed an update for this story.

Her doctors had talked about trying to get her into the Mayo Clinic.

In a testament to the drive of people who choose to run grueling obstacle courses time and time again, some of the ninjas she trained with for “American Ninja Warrior” work at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and contacted cardiologists themselves, asking the doctors there to look at her case.

She now has an appointment scheduled.

“It’s amazing when life comes full circle,” Hannah wrote.

Contact staff writer Kyrie Long at 459-7510. Email her at klong@AlaskaPulse.com.