A disease once thought eradicated in the United States is back again following outbreaks in 12 states, leading to the death of at least one child, health officials say.

More than 200 measles cases have now been confirmed, including one confirmed fatality from the disease and a second suspected fatality, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest data, as of March 7.

Those under the age of 19 have been hit the hardest, accounting for 79% of cases so far in 2025, the CDC says.

While the vast majority of cases are among people who had not been vaccinated, those who received the measles vaccine in their childhood may be wondering about the shot’s longevity and effectiveness later in life, including whether there is a booster for adults.

Here are five things to know about navigating the measles outbreak.

Where are the measles outbreaks?

Health officials have confirmed measles cases in 12 states: Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Texas and Washington, according to the CDC.

The largest outbreak is in west Texas, where more than 20 people have been hospitalized so far and where the first measles death since 2015 was recorded, according to Harvard professor Robert Shmerling.

A few cases have been confirmed in previously vaccinated people, but the other 94% of cases are among unvaccinated people, primarily children, the CDC says.

The majority of hospitalizations from the disease are among children under the age of 5, and the confirmed measles fatality in Texas was a “school-aged” child, according to Texas Health and Human Services.

The second death under investigation in New Mexico was reported as an unvaccinated adult, the New Mexico Department of Health said.

In comparison to last year, there were a total of 285 measles cases reported in 2024, including 120 in children under 5, 88 in children and teens and 77 in adults older than 20, according to the CDC.

Of those, 89% of cases were among unvaccinated individuals.

When are measles vaccines recommended?

Two vaccines against measles are available and recommended in the United States.

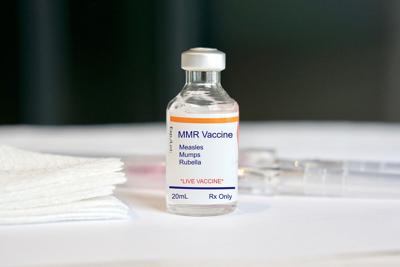

The MMR vaccine includes protection against measles, mumps and rubella. The MMRV vaccine adds varicella, or chickenpox, to the same regimen, according to the CDC.

Both vaccines are recommended as part of the regular childhood immunization program with other shots, the CDC says, and deciding between the two should follow a discussion with your child’s health care provider.

The MMR vaccine is given in two doses in early childhood. The first dose is given to infants aged 12 to 15 months, and the second dose is given to kids aged 4 to 6 years, according to the CDC.

If children were not vaccinated on this schedule, doctors may recommend the vaccines later in life, and infants traveling internationally can get both doses before their first birthday, the CDC says.

The MMRV vaccine is approved only for children between the ages of 12 months and 12 years, and includes a 12-to-15-month dose and a 4-to-6-year dose. The second dose can be given as early as 3 months after the first dose if needed, the CDC says.

If you haven’t ever been vaccinated, the MMR vaccine can be administered to someone in the first 72 hours after they were knowingly exposed to measles and that can offer some protection against the worst symptoms of the disease, according to the CDC.

How long are measles vaccinations effective?

If you were vaccinated as a child, you most likely will not need another shot as an adult, the CDC says.

One dose of the MMR vaccine has been found to be 93% effective against measles, and a second dose raises the effectiveness to 97%.

While the vaccine is effective, it doesn’t mean you can never be infected with measles. Effective means you are less likely to become infected, but even if you do, the symptoms will likely be milder and you are less likely to spread the disease to other people, according to the CDC.

“Some vaccinated people may still get measles, mumps or rubella if they are exposed to the viruses,” the CDC says. “It could be that their immune system didn’t respond as well as they should have to the vaccine; their immune system’s ability to fight the infection decreased over time; or they have prolonged, close contact with someone who has the virus.”

Measles is highly contagious and spreads more easily than the flu, COVID-19 and even Ebola, according to Harvard Medical School.

Communities therefore are most easily protected through herd immunity, meaning enough people are vaccinated against measles in a given area that the disease is unable to spread even if the few unvaccinated people are infected.

Didn’t we eradicate measles in the U.S.?

While measles was first observed and recorded by a Persian doctor in the ninth century, the disease wasn’t a nationally notifiable disease in the United States until 1912, according to the CDC.

Between 1912 and the 1960s, when a vaccine was developed, nearly all children got the measles before the age of 15, infecting between 3 and 4 million people per year, the CDC says.

Each year, these infections led to 48,000 hospitalizations, 400 to 500 deaths and 1,000 cases of encephalitis, or brain swelling.

Then, in 1954 measles was successfully isolated from the blood of a 13-year-old and could be used for vaccine development, which came a decade later, the CDC says.

A weak vaccine was licensed in 1963, but a stronger, more effective vaccine was created and approved in 1968, according to the CDC. This vaccine is the same strain used today, though the shot is now combined with vaccines against mumps, rubella and varicella to create the MMR and MMRV shot.

The shot was so effective that a vaccination program dropped measles cases 80% between 1980 and 1981, according to the CDC.

Case numbers continued to decline until measles was declared “eliminated” in the U.S. in 2000, meaning the continuous spread of the disease was stopped for more than 12 months, the CDC says.

This doesn’t mean that there were never any cases, but they were considered isolated and those with the disease may have been infected outside the country. This success was directly attributed to the high vaccination rate of children, which has since wavered and allowed an “eradicated” disease to return.

What are the signs and symptoms of measles?

“Measles is a highly contagious viral illness that typically begins with fever, cough, coryza (runny nose), and conjunctivitis (pink eye), lasting 2-4 days prior to rash onset,” the CDC says.

The virus is spread through direct contact or through the air from an infected person’s breathing, coughing and sneezing, the CDC says. The virus can stay infectious in the air and on surfaces for up to 2 hours.

“Infected people are contagious from 4 days before the rash starts through 4 days afterward. The incubation period for measles, from exposure to fever, is usually about 7-10 days, and from exposure to rash onset is usually about 10-14 days (with a range of 7 to 21 days),” the CDC says.

Anyone who suspects they may have measles, or knows they have been exposed to measles, should isolate themselves in a private room and alert your doctor. A test will be issued to confirm an infection, typically a nasal or throat swab.

Doctors may then recommend an MMR vaccine if you have never been vaccinated or will provide additional care. Measles does not have a specific antiviral therapy.

Anyone with a fever of more than 101 degrees Fahrenheit with an associated rash and cough, and if they traveled internationally or to a measles hotspot in the United States, should be tested for measles.