This is not an uncomplicated, easily digestible book of poetry. Annie Wenstrup’s debut collection, “The Museum of Unnatural Histories,” is a personal exploration of fragmented history, offering an intimate look into the complexities of generational pain, colonial violence and girlhood.

Wenstrup, who lives in Fairbanks, stages an intriguing approach in this work — taking her intimate, deeply personal poems and formatting the book as if they are on display at a museum. Wenstrup writes in her acknowledgements about her discovery, through Dawn Biddison of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, “that the museum is not the housing of artifacts. Instead, it’s an environment that fosters the possibility of encounter.” In her collection she turns what could simply be static memories into an experience for readers to partake in, transforming the reading experience from simply the turning of pages into a deeply personal exploration of both a personal and collective history. She challenges the traditional role of the museum visit, turning it from a distant, impersonal activity into a reflective and thought provoking encounter between self and the “exhibits.” Through this innovative approach, her poetry becomes a living, breathing dialogue between the past and the present, between what was and what might still be.

One cannot help but notice a persistent and recurring feeling of loneliness and alienation underlying Wenstrup’s poems. This solitude is only heightened by their exposure, placed on display where an audience can gaze but never truly see. In reading these poems, one is confronted by a sense of voyeurism. Wenstrup’s vulnerabilities are laid bare, yet they are consumed, dissected and enjoyed by the average museum-goer, a process that feels uncomfortably akin to the nation’s historical exploitation and tokenization of its First Nations people. The opening poems of this collection are a reflection and critique upon the inevitability that as stories get told, they are distorted. Sukdu, Wenstrup will go on to write in her native Dena’ina language, are stories but with time they become sukdu’a, a story that has changed enough to become a personal story. As she enters the museum she sees those distorted stories of Indigenous history, feeling she “won’t appear human here” and hates the feeling of “seeing myself reflected in those layers of paint.” In her collection of poems, Wenstrup is able to now turn the lens inward, allowing herself to be the curator of her own exhibit for once — reclaiming the portrayal of a cultural narrative that has long been controlled by non-Indigenous voices.

This is not an easy read. Wenstrup tackles heavy, challenging topics that are far from simple or digestible. Colonial violence, the weight of inherited trauma, and the raw complexities of family life are not things to be skimmed over or simplified for convenience. The rawness of her words demands space and contemplation, refusing to offer easy answers. It would be a disservice to reduce these deeply emotional experiences into something easy to swallow, and Wenstrup resists that temptation throughout the collection. Each poem carries weight, not just in its content but in its refusal to shy away from discomfort. The collection has to be read in its entirety to be fully understood, for each poem is deeply interconnected with the other. We watch recurring themes — luck, hibernation, metamorphosis, disreality — weave their way into her work creating an understanding that can only come on the second or third read.

Her portrayal of the transition from girlhood to womanhood — along with the grief and loss it entails — resonated deeply with me. The weight of societal expectations, particularly those imposed on her as a Native woman, is starkly present in Wenstrup’s poems. They capture a profound disconnect between the version of femininity the world demands and the identity she is struggling to embrace. We can trace the abrupt loss of innocence and the youthful wonder Wenstrup feels in deep correspondence with her yearning to feel trusting and in awe of the world again. In her poem “As Girl,” Wenstrup writes, “The goat-like pupil reflected a parade of women and girls like ewes. Fair and Lovely. I thought they were adored. Later, I was not a girl anymore.” She captures the pain of realizing that women, especially Native women, are often viewed not as individuals but as commodities, valued solely for what they can provide.

My favorite poem in the collection, “Excerpt: 25 Years of Tiny Power,” captures this further in a conversation with Polly Pocket, who despite reflecting upon the magic of her time with our author, says, “I saw how I must appear, covered in fingerprints, unable to move myself.” Like Polly, who is confined to her tiny, controlled story, the woman is similarly molded by societal expectations — shaped, handled, and ultimately trapped in a world of others’ making. The meta nature of this comparison becomes apparent — just as Polly was designed to be controlled, women are often trained, from an early age, to perform according to the rigid roles assigned to them.

A quote from the poem “Intermission” perfectly captures Annie Wenstrup’s gift of merging the ordinary with the divine, serving as a reminder to slow down and appreciate the little joys of our lives: “While I drink a coffee with cream, tender plant and I watch the world move around us.”

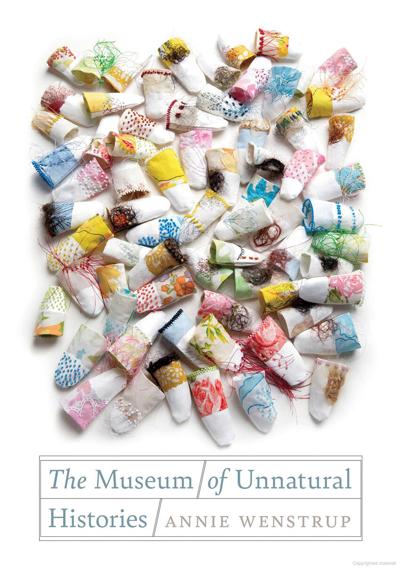

“The Museum of Unnatural Histories”

Wesleyan University Press

Libby Rhodes is a reader and poetry lover who lives in the boreal forest just outside of Fairbanks. She can be reached at libbyrhodes721@gmail.com.