‘It is difficult, if not impossible, for any person living in Canada today, Inuit or non-Inuit, to imagine what it was like to live as Inuit traditionally did,” Noel McDermott, one of the editors of “Unikkaaqtuat: An Introduction to Inuit Myths and Legends” writes in the introduction. “The sheer vastness of the land, the extremes of climate, the long winter nights, and the lack of contact with other peoples created a fertile imaginative. Gathered around the dim light of the qulliq, the stories being told assumed a power of their own and became part of everyday life and experience.”

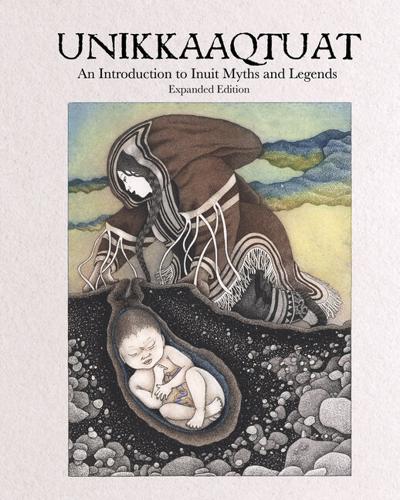

McDermott, along with Neil Christopher, Louise Flaherty and artist Germaine Arnattaujaq, has spearheaded a project gathering Inuit mythology into this collection that sheds substantial light on a tradition that took form among people who were dispersed thinly and widely across the Arctic coast of North America, and who, like people everywhere, envisioned a cosmology rooted in the world they knew, and that, in return, explained that world to them.

If, McDermott, adds, “the reader accepts the premise that these stories had two main purposes, to entertain and to teach, then it is possible to begin to understand that there is a consistently implied message throughout. Behind all the described chaos, violence, and gratuitous cruelty, the stories point to what the norm is and ought to be.”

“Unikkaaqtuat” is published by Inhabit Media Inc., a Canadian Inuit-owned press seeking to both preserve and share the cultural traditions of the Inuit people with children’s and adult books. This book lies on the adult end of the spectrum, though it is acceptable for teens. The tales here range from creation stories, accounts of great adventures, and yarns involving talking animals, themes so common to the world’s varied mythologies, to moral lessons, also a mainstay of traditional storytelling, and famine and starvation, a central aspect of a subsistence life drawn from a homeland lean in food.

Creation stories extend beyond the earth and into everyday phenomena. And frequently throughout the book, where tales have been gathered from a geographically huge region, more than one version of a story is told. Thus we learn that thunder and lightning were once human siblings, a boy and a girl, although how they became powers from the sky varies between two different stories. In one they are abandoned orphans seeking revenge, while in another they are left unattended and get into trouble, then become the entwined powers of sound and light to flee punishment.

Punishment can come in many forms, such as retribution exerted by forces beyond the immediate human world, as well acts of revenge. Sometimes these two reasons join forces, as they do in “Papik,” the story of a man who murders his brother-in-law. His mother-in-law then dies and comes back a a revenant, a ghost, to avenge the loss of her son. Unusual among these stories, the moral of this one is offered as its closing paragraph: “As our fathers used to say: when anyone kills a fellow creature without reason, a monster will attack him, frighten him to death, and not leave a limb of his corpse whole.”

Violence is rampant, murders are frequent, and strangers often untrustworthy. The story of Atanaarjuat is particularly bloody. He flees his village with his brother because the other men are jealous of them. His brother is caught and killed, and Atanaarjuat plots his revenge, clubbing to death all of the men responsible and taking in their women and children.

Trading sexual partners is another recurring theme, a common practice that bedeviled missionaries when they arrived from Europe. Even in a place where its practice was not frowned upon, however, it does not always end well. In “The Man Who Took a Fox for a Wife,” one man marries a fox that has transformed herself into a woman, while another marries a likewise metamorphosed hare. They exchange wives but it goes awry. And then a worm clothed as a man enters the story, seeking his own revenge.

Animals changing into humans and vice versa can be found throughout the book, their presence in the stories reflective of the belief that at one time animals could talk, and their relationships with humans were close. In “The Soul,” an old woman who has died is eaten by a raven, and from there her spirit moves to a dog, then a caribou, and onward, her soul passing from one animal to the next as she flows through the different land, sea, and air creatures that inhabit the Inuit world. Eventually she finds her way into another woman and is then reincarnated as that woman’s child.

Spirit beings fill the landscape, some benevolent, others malevolent. The Ijirait help two Inuit women, while nakasungnaikkaq are known as man-eaters and Narajat are gluttons. The Inurluit are not human, but, “never do any harm to human beings; they have no thought of enmity. They live down by the salt sea, where men have met with them in times long past.”

And sometimes the stories are simply adventures undertaken by heroes. The saga of Kiviuq is a sort of Inuit Odysseus with perils, strange beings, and sometimes violence meeting him at every turn in his travels.

Strangely missing is Sedna, the goddess of the sea central to so many Inuit legends. The most globally known personage in northern cosmology she is so famous that a dwarf planet bears her name. Why stories of her are not found here, the editors do not say. But it is an unexpected hole in an otherwise wide ranging survey of this too often overlooked mythological literature.

Looking at Inuit myths through modern eyes, McDermott, who has carefully annotated this volume, writes that one finds that while “they are entertaining and give the reader a glimpse into the traditional world of Inuit, they also provide useful lessons on how we might live in a world that appears to be growing more chaotic, unpredictable, and dangerous.”

That’s what “Unikkaaqtuat” delivers.

David James is a freelance writer who lives in Fairbanks. He can be emailed at nobugsinak@gmail.com.